Introduction

One Size Fits All?

Software is complex and unpredictable. We don’t know exactly what it looks like when we are done – in fact it’s never done. We know even less, about what our customers are actually going to do with it. Jeff Gothelf, Author of Lean UX

As technology advances, we get in touch with user interfaces (UIs) more and more on all kind of day to day activities.

Today and in the future, we will find more of them on our refrigerators, alarm clocks, remote controls and in our cars. As designers and developers of these UIs, we are in charge to reduce complexity, to make information understandable and the interaction with these systems more accessible. For the past, design techniques such as universal design (Mace et al. 1990), design for all (Stephanidis 1997), and inclusive design (Keates et al. 2000), relied a lot on an average of users while making major design decisions. We tried to make one UI design fit as many people as possible, but after all, humans are different. Additional a UI is never independent from the whole context of use, defined by two more components (environment and platform) besides the user (Zimmerman et. al. 2014). Because of the wide variability in the context of use, developing tailored interfaces according to the need of an individual user was impossible before. Now the abilities of today’s network information technology brings us closer to the day we will be able to create rich, immersive personalized experiences by tracking interactions and aggregate and analyze them in real time.

The data collected by the sensors we carry around in our pockets, on our wrist and on our heads (Spectacles by Snapchat or Google Glass) all day, provides us with opportunities like never before. Their aggregation will help us to design systems which will offer a better user experience (UX) than non-adaptive systems (Yigitbas & Sauer 2016).

Computer scientist and researchers call those systems “adaptive“. This term refers to the process in which a system adapts to an individual user, based on the context of use. The ambition of adaptive systems is not only that “everyone should be computer literate“, but also that „computers should be user literate“ (Browne, Totterdell, & Norman 1990). Adaptive systems are a crowded research space and have been long-discussed in academia of computer science. Since the early days of personal computing, scientists have done research on the challenges and opportunities of systems which proactively support the user. „The main goal of adaptive systems is to increase the suitability of the system for specific tasks; facilitate handling the system for specific users, and so enhance user productivity; optimize workloads, and increase user satisfaction.“ (Oppermann 1994). Besides, a lot of research is done on Artificial Intelligence (AI), e.g. Machine Learning (ML) or Neural Networks, which proactively supports the development of adaptive systems.

For a long time, these systems trying to help the user were hard to get right, because they have a high cost of computing power and a deep need for all kinds of data. The enormous growth in computing power, the rise of connectivity, the widespread availability of mobile internet connection and mobile devices these days bring us closer to a point where the dream of unique user interfaces for unique users may become reality.

The sensors of our smart devices enable soft ware to under- stand the users, their behavior, habits, preferences and environment more detailed than ever before. This development comes along with an explosion of new opportunities and challenges for designers. The context of use has become one of the main topics in the age of mobile computing. This is proved by the development and evolution of terms like ”Responsive Design“ in the last years. Soft ware isn’t used only at one device and at one desk anymore. Soft ware is used across different devices, outside, on the go, at parks, subways, at home before bed — or even in the morning under the shower (Figure 1).

Besides the diversity of users and context of use, the content, and the scope of information to be dealt with, is also more diverse than ever. Rich Ziade, CEO of Readability, once told in an interview: “The mobile browser is no longer the sole destination of the hyperlink. Stuff opens inside of Twitter, Facebook, etc., and that means that content needs to be ready to go all the new contexts.” (McGrane 2012) This requires a huge flexibility of content for all kinds of contexts (Nagel 2016). Intelligent user interfaces have been proposed as a means to overcome some of these challenges that direct manipulation interfaces can’t handle (Höök 2000). The design of the algorithms that determine the behavior this intelligent or automated systems, will be the next step in human-centered design, as Harry West from Frog Design argued in an interview with Fast Company (Woods 2017).

— So let‘s dive into it!

User Interface Evolution

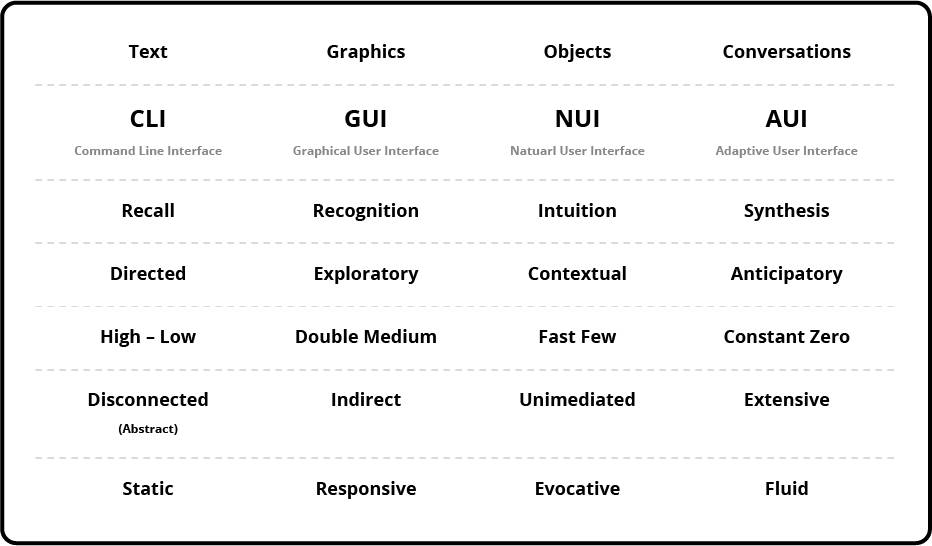

When thinking about the future, you first have to look back. You can divide the history of UIs into four stages. As prompted by Wixon (2010), these four stages are Command Line Interfaces, Graphical User Interfaces, Natural User Interfaces and Organic User Interfaces.

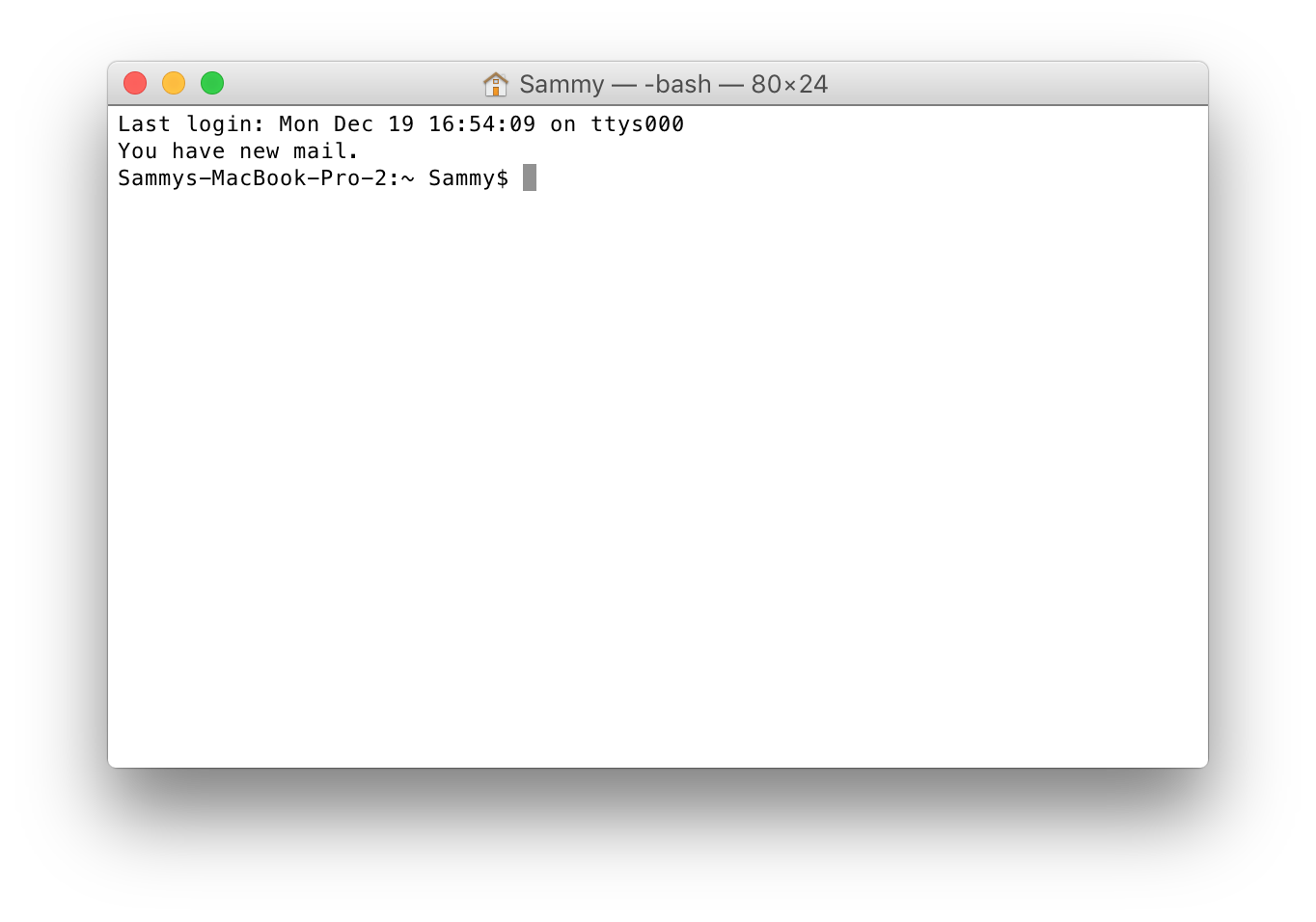

Command Line Interfaces

The first Command Line Interfaces (CLIs) were basically texts on a screen. You as a user had to recall the command. What you typed was either accepted by the machine or not. There was little or no prompting if it will do what you want it to do. Those systems were directed, everything was up to you. The systems did nothing without an explicit command from the user. A CLI was what Wixon (2010) calls High – Low: a high number of possible commands and a relatively low support of what could be done with those commands. They were disconnected, and the will was expressed in abstract terms. These terms oft en had to be learned and only made sense for the machine. CLIs were static as they waited for the users to perform an action.

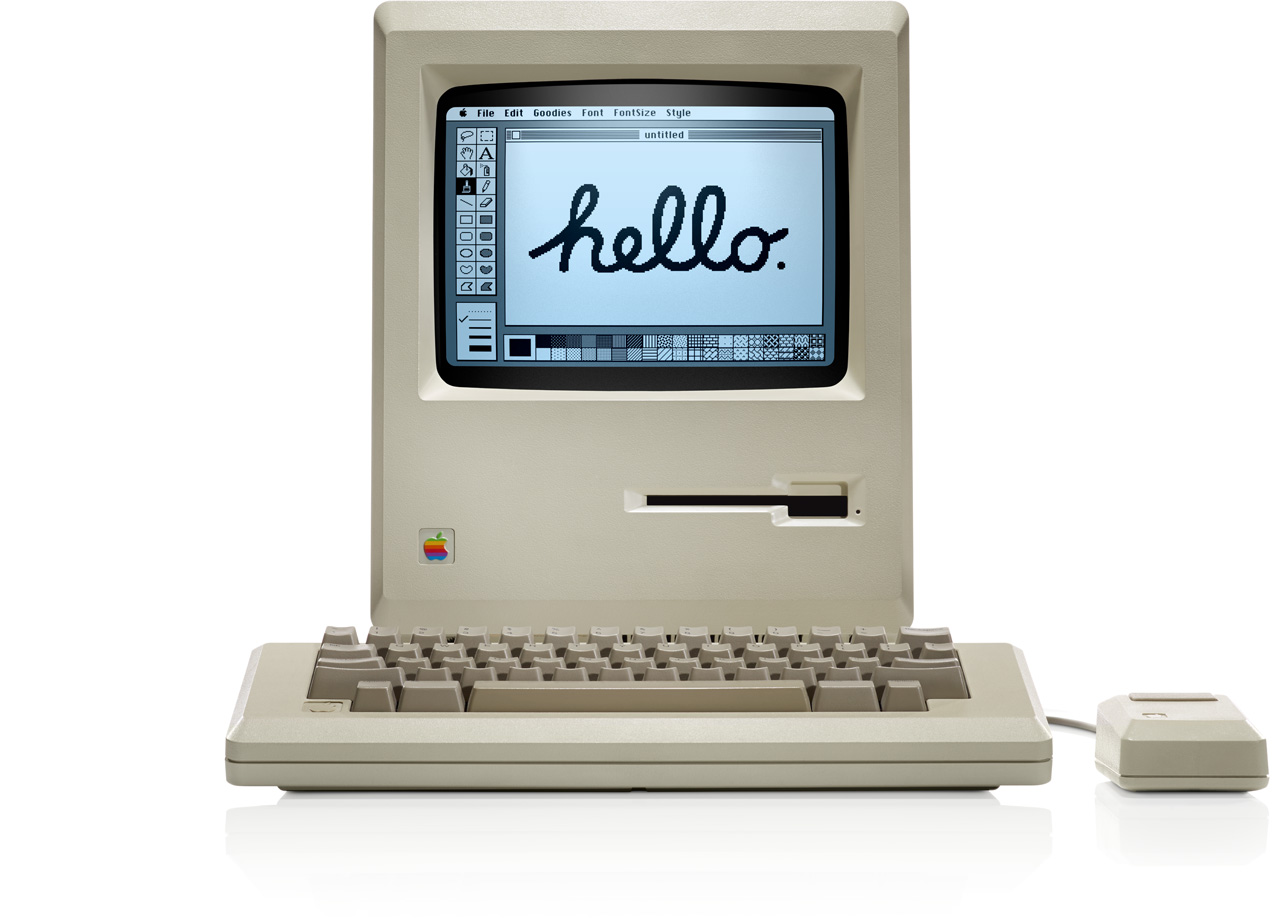

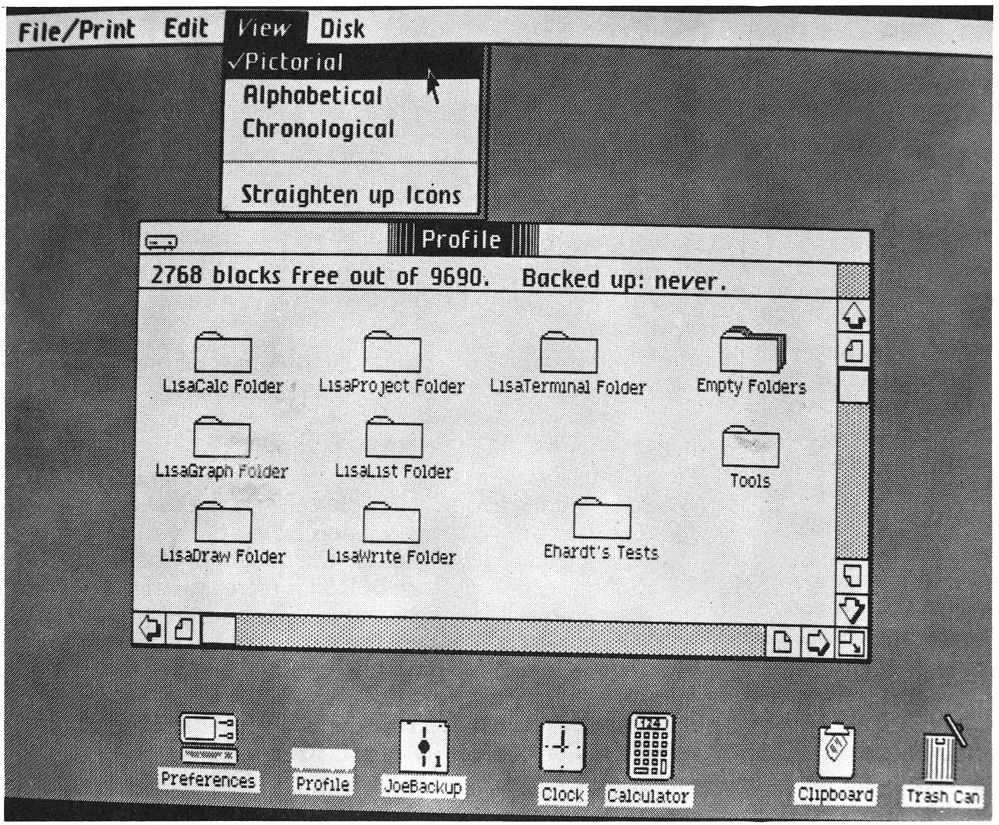

The Macintosh moment

With the introduction of the Apple Macintosh in 1984, the age of Graphical User Interfaces began. This was a breakpoint in the history of computing. For the first time, Apple used a point and click device, a computer mouse, and a keyboard to trigger more interactions than simply setting the cursor or mark text for copying like in the CLIs before. This was done by using metaphors in a visual manner, like the desktop and paper icons for documents.

Graphical User Interfaces

You are able to remember commands to interact with the system by knowing where to find them. You don’t have to remember everything, you just have to recognize what’s relevant for you to complete your task. The systems are exploratory, which means you can explore possible ways to interact with the system, e.g. by pulling down a menu. You can see what a system is capable of doing and try things out. To undo commands allows you to explore actions because you know you can always go back. Wixon (2010) calls those interfaces double mediums, which means they have a high number of commands and provide the user with some sort of support by showing them. These interfaces are indirect, as you interact through keyboard and mouse. You trigger pull down menus and hover over things. They are responsive, just click the mouse down and you get a response, e.g. a drop down menu with more functionalities (Wixon 2010).

Natural User Interfaces

According to Wixon (2010) GUIs and the way of indirect interaction, through mouse and keyboard, were standard until the introduction of touchscreens and multi touch on a variety of devices. What followed were the Natural User Interfaces (NUIs). NUI systems are all about direct manipulation of objects. The interface triggers your intuition. The things you naturally do tend to be the things that work. NUIs are contextual, meaning that the behavior of objects will make sense in the context, e.g. some images are piled, so it make sense that you can grab and drag the image on the top first. There is a relatively low range of commands, but they act fast – often instantly – because natural user interfaces rely on natural interactions like grabbing and scoping and are to immediately respond to your manipulation. By using these interfaces with your hand or your whole body movement, they are so-called unmediated. Lastly, they are evocative, which means they bring forth the behavior that leads to success. The Microsoft Surface Table is an example of a NUI system (Wixon 2010).

Next generation User Interfaces

What follows is what Wixon (2010) calls Organic User Interfaces. In all his descriptions, of the different user interfaces, the descriptions focus on the core of the interface, the things that you interact with. He describes text as the main type of interaction in the CLI, graphics in the GUI and objects in the NUI. In alignment to those three types of interaction, I recommend to use the term “conversations” instead of Wixons (2010) descriptive term “organic” for the main type of interaction in the next generation of interfaces. Conversations align more with the other terms he is using to describe the main type of interaction in the development process of user interfaces. I propose to replace the element of the name, organic with adaptivity, as my work focuses on adaptivity. I recommend to use this term for describing where interfaces are heading. So the next generation of interfaces will be Adaptive User Interfaces (AUI). Wixons (2010) on-going description matches well with my correction of the name and main type interaction (Conversations). With AUIs, the main interaction is happening in a conversation between you (the user) and the system. It is a conversation, because you tell the interface what you like, what you dislike, and what you are going to do next. This happens both directly and indirectly just like in a conversation between humans. Based on this conversation an adaptive system interprets and predicts your behavior. Humans do it by using their senses and intentions, learning to interpret situations. Systems do it by sensors and analysis, also learning how to interpret situations. This is why conversations instead of organic is the right term for the next generation of interfaces, called Adaptive User Interfaces.

An AUI builds a synthesis with the user, as it gets to know you and adapts to you. These systems are speaking to you and predict actions before you fulfil them. This makes them anticipatory. Wixon (2010) describes them as constant zero, that means they are always available, you always interact with those systems. E.g. the system gathers location and movement data in the background without you recording them actively. AUIs are extensive to the users, they enhance them, support them and help them to be more efficient. These interfaces that adapt to the users have to be fluid. Fluid in a way to provide the flexibility to adapt to the specific context of use over and over again, to be able to change constantly.

With this description I’ve provided a basic concept to understand what the next generation of UI is and what their capabilities are. I have to name that all of this UIs are extensions of capabilities of the UIs before. As you know you will find text to interact within GUIs and graphics are what makes most objects appealing in a NUI. This means you will find elements of CLIs, GUIs and NUIs in AUIs. Adaptive UIs fall back to the principles of their predecessor interfaces often, but extend those with new possibilities whenever possible. In the next chapter I will dive into artificial intelligence and explain why this term and the technologies behind are crucial to the evolution and development of AUIs.

AI first world

[…] we are evolving from a mobile first to an AI first world. Sundar Pichai, CEO at Google, 2016 at #madebygoogle

Sundar Pichai, CEO at Google, stated in his presentation “#madebygoogle” on October 4th 2016, “[…] we are evolving from a mobile first to an AI first world.”

The evolution and research done on Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology is crucial to the development of AUIs. This is because most of the techniques used to proceed and understand the data to deliver a truly unique experience use some sort of technology which is summarized under the greater term AI. But what is this magical term AI we hear about in sci-fi movies and books? Does it mean machines are taking over? Don’t worry, that’s not what’s happening here. Let me explain. First, you have to know that today there are three main driving technologies within the field of AI:

- Natural Language Processing (or Speech Recognition)

- Machine Learning (ML)

- Neural Networks (e.g. Deep Learning; a technology that use ML)

On the following pages I will describe each discipline and line out the essentials of each technology for everybody to understand, not too techy.

Natural Language Processing

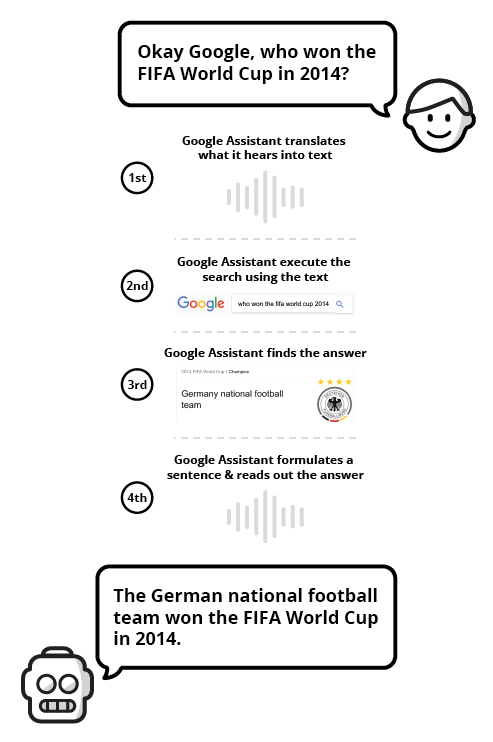

Research in understanding the complex human language and sentence structure is the key driver of artificial intelligence. Talking to technology, as we do in human-human communication, is widely considered as the best way to interact with an AI System. Natural Language Processing or Speech Recognition is the technology that enables devices to understand text or voice commands from humans, and lets us have a human-like conversation with technology.

We made this [Google Search] for everyone and today me make this [Google Assistant] just for you. Voice in Google Assistant promotion video, 2016 at #madebygoogle

Take, for example, the Google Assistant: it can be asked a question through speech. What it does? It recognizes you talking to it and then translate your words into a text query using natural language processing. The assistant then uses this translation to find the answer to its understanding of your question. Once Google Assistant found a suitable answer, that it thinks matches its interpretation of the question, it constructs an understandable sentence that includes the answer, and reads it out loud (Google 2016).

Machine Learning

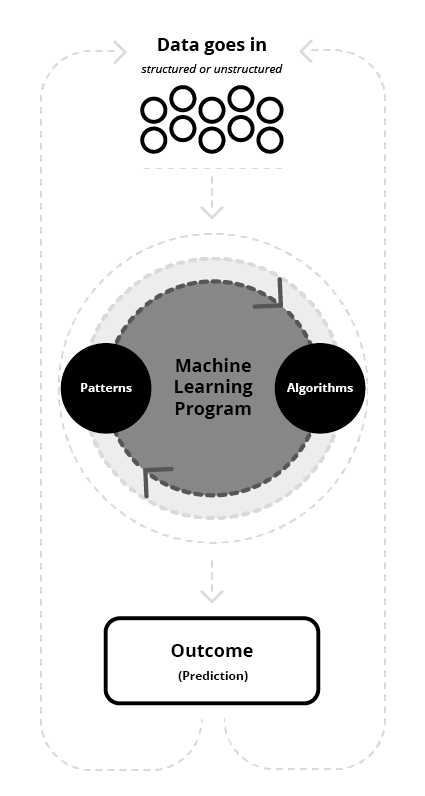

Machine Learning is the state-of-the-art technology behind most of today’s AI programs. Rather than explicitly program a computer, everything it has to know about the world, ML enables a computer to learn for itself. ML relies on a lot of data and is able to make sense of it on its own. Basically, ML programs try to find patterns, make predictions based on those patterns – imagine it does it like cardsorting on a wall.

For example Facebook‘s news feed uses machine learning to personalize the content you see. Imagine you often stop scrolling to read or interact with a particular type of post, e.g. from the same person or page. The software behind the news feed then uses statistical analysis and predictive analytics to identify patterns. These patterns are basically predictions of relations between your interactional behavior and the content you’ve interacted with. Based on this data the software decides to show you more often what it thinks (interprets) you like to see. For example in case you often “like” posts from a particular friend, the software may predict that you like to see more of this person and starts to show his or her posts earlier in your feed. If there’s a behavior change e.g. you stop to read posts of a particular friend, the software recognize and regarding to the new set of data adjust its prediction on what you may like (Rouse 2016).

Neural Networks

A Neural Network program basically tries to replicate the way the human brain works. It uses machine learning to recognize, for example, images and tries to make sense of them by classification and pattern recognition.

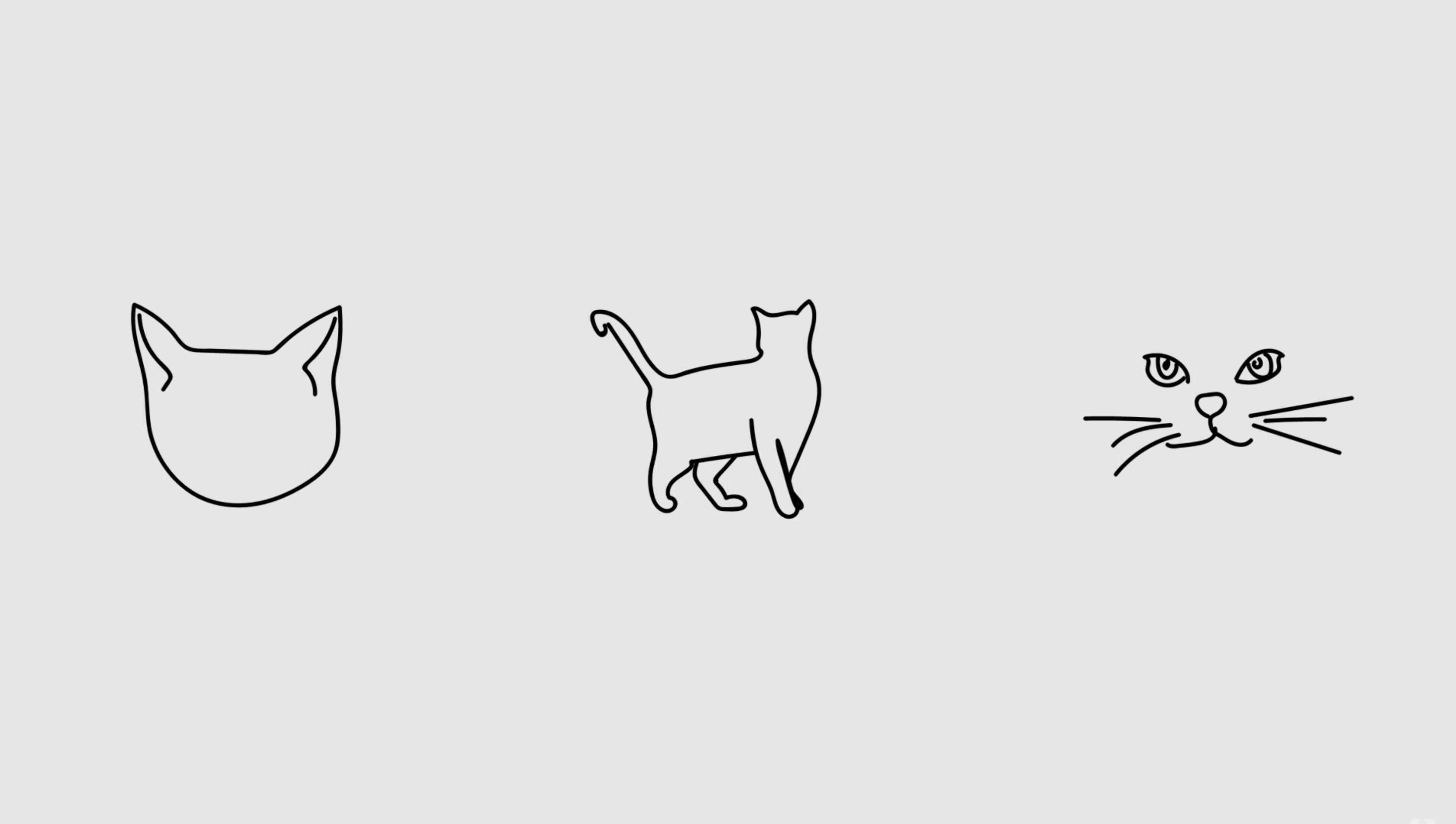

An example you can actually play with is Googles Quick Draw (see Figure 12). Quick Draw uses machine learning to build a neural network which predicts what you drew based on how you drew it and how others drew it. It gets smarter over time by learning how humans draw things in different ways. For a human it is simple to say those three drawings are cats (see Figure 10), but for a computer they are totally different. In order to let a computer understand that those three drawings are cats you have to show it a lot of different doodles of cats (see Figure 11) until it starts to recognize patterns, e.g. that all cats have pointy ears, a small nose and whiskas. The more doodles it sees, the better it gets at predicting a cat doodle (Google Developers 2016).

Applicability to adaptivity

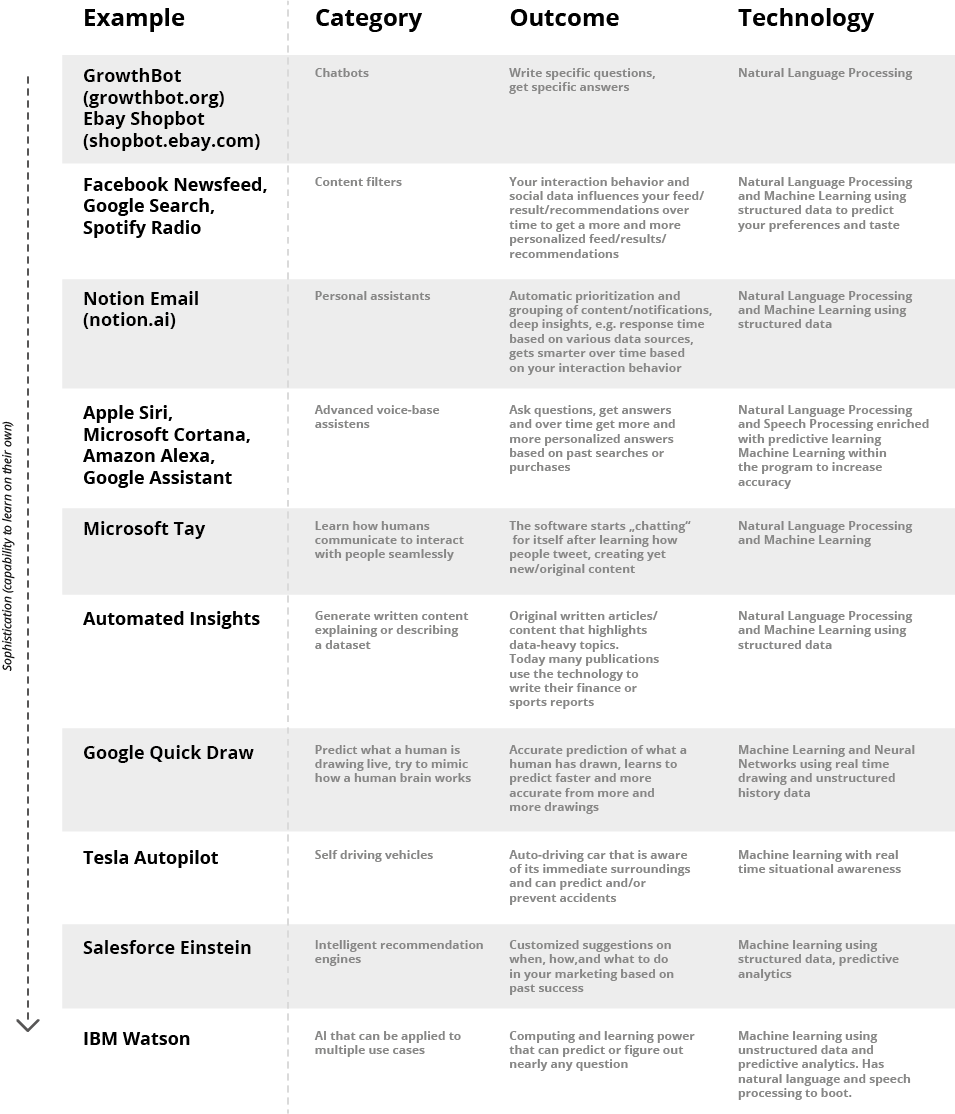

The combination of those technologies are what enables a system to analyse and make sense of, e.g., movement, traffic and calendar data result in recommending you to leave early with your car in order to be on time for your next event in the calendar. The data collected from Natural Language Processing helps to understand natural human language better. Today those systems often seem dump, but the more we talk to them the smarter they will be in the future. Each speech instruction we give, for example Alexa from Amazon, helps the system to make greater sense of how humans communicate with it. The learning from analysing today’s speech input results in an optimization and growth of capabilities of the system in the future. Machine Learning algorithms are what causes most of this learning by the software trying to itself make sense of the data. Instead of by human teaching, the system learns independently how to adapt and understand the user’s input, e.g. through algorithms, to make sense on its own. This enables a system to deliver unique solutions to a problem which even the developer of the algorithm could not foresee. In today’s interfaces, you see this kind of ML in the word prediction of you keyboard on mobile devices, automatic recommendations on the time to leave and suggestions like restaurants based on a lot of data points, e.g. location, social and user history data. Neural Networks are the crown discipline of AI, they are a more advanced ML technology and feel magical. As stated before, Neural Networks try to mimic the way a brain works. This results in even more unpredictable results than ML produce. While the developer of ML controls the algorithms, Neural Networks are capable of developing algorithms on their own to enhance their learning process. What follows is a short table that outlines some examples of today’s AI technology applications ordered by the capability to learn on their own. The examples show the outcome and illustrate which AI technologies are applied (see Figure 13).

Consumer readiness of AI technology

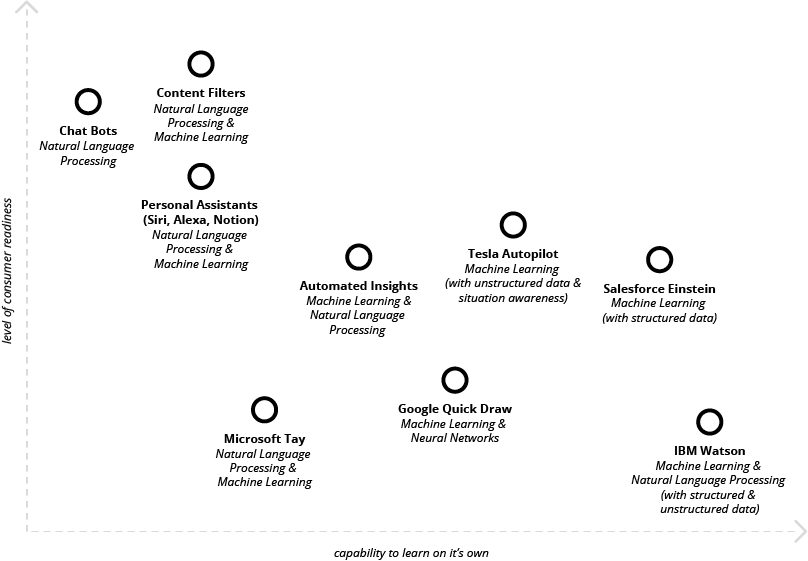

To illustrate the consumer readiness and mass appeal of today’s AI technology I use a two axis diagram based on the “Simplified AI Landscape” map from Hubspot Research. This simplified mapping is expanded and revised. The technology is mapped between the level of consumer readiness and capability to learn on it’s own. The x-axis illustrates the level of technological sophistication the AI technology has. The y-axis represents the mass appeal of the technology, e.g the consumer readiness (see Figure 14).

Such an illustration is considered to be subjective and never completely correct (Wilson 2013). Due to another point of view, these examples may vary in their positioning. However, I recommend this diagram as a useful tool for understanding the landscape of AI technology.

Sum it up

The evolution of AI technology, Natural Language Processing, Machine Learning, and Neural Networks is crucial to the development of adaptive user interfaces. Most technologies which enable these kind of interfaces to deliver truly unique experiences are summarized under the greater term AI. It is important to understand that those technologies are still getting explored and most of them are not consumer ready yet, if it comes to a certain level of sophistication. Nevertheless, as designers and developers of those interfaces it is necessary to understand these technologies, not in detail but to a certain level. „They lack a tacit knowledge of ML as a design material. Today UX teams either never consider adding ML to enhance their designs or they think of them too much like magic and generate ideas that cannot be effectively implemented.“ (Yang et al. 2016, p. 10) Think of it like, graphic designers need to know their material like paper and print techniques, UX designers today need to know what the possibilities are AI can bring to enhance the user experience. Because you can’t design for a medium which capabilities you don‘t fully understand.